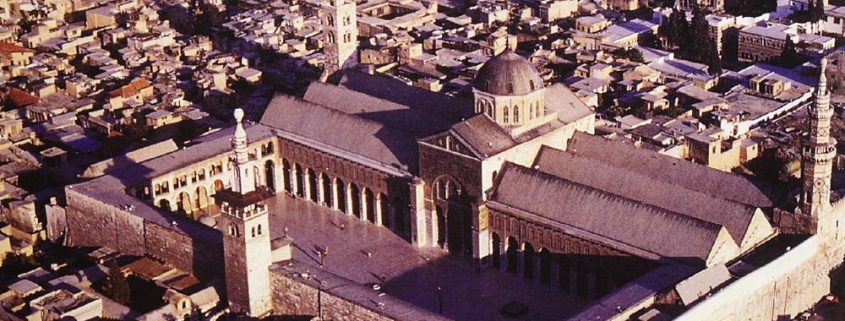

Great Mosque of Damascus

Annie Labatt | Orignially published in Metmuseum.org

In an address to the citizens of Damascus, the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I (r. 705–715) proclaimed: “Inhabitants of Damascus, four things give you a marked superiority over the rest of the world: your climate, your water, your fruits, and your baths. To these I wanted to add a fifth: this mosque.”1 The construction of the Great Mosque (or Friday Mosque) of Damascus was a means of establishing the permanence of the Umayyad rule, a significant gesture in a city that had been under Persian rule from 612–628 and then Arab rule from 635–661. Museum

Al-Walid chose a site that was already considered holy: it had originally housed a temple dedicated to the Syrian storm-god Hadad, which was replaced with a Roman temple dedicated to Jupiter Dolichenus, which was in turn replaced with the Church of John the Baptist. Al-Walid bought the church and promptly demolished it, leaving only the inner walls of the original temple,2 which became the entrance to the mosque.

The mosque was unlike any before it, and its form was mirrored by later imperial mosques. Four minarets (all from different time periods) sit atop the four corners. Unlike earlier mosques, this structure’s rectilinear proportions created a vast empty space. On three sides of the court there is a single-aisled portico. The fourth wall (known as the qibla3) has a long prayer hall that, similar to a Christian basilica, has an east-west axis. This prayer hall has three aisles that run parallel to the qibla wall and an axial nave that runs perpendicular to it. A pitched roof is aligned at right angles to the direction of prayer.

Details of the mosaics on the western courtyard wall from the Friday Mosque, Damascus, 705–715. Left: Detail showing a pastoral scene punctuated by tall trees. Right: Detail showing a fanciful pavilion with hanging pearl chains. Photographs: John Wreford / Courtesy of Finbarr B. Flood

Of particular importance are the mosaics that decorate the mosque. Attributed to Byzantine workmen, these mosaics appear on the prayer hall, the inner side of the perimeter walls, and the court facades. Flowing rivers, fantastic houses, and richly foliate trees of variegated greens ornament the golden background. The motifs in these mosaics are similar to those of the Dome of the Rock, which predate this monument by fifteen years. Finbarr Flood has suggested that the meaning of these verdant mosaics is related to passages from the Qur’an quoted in inscriptions on the walls.4

The vibrant sense of nature as a source of life and activity suited the function of the mosque as the central meeting place for the citizens of Damascus. The monument functions specifically as a Friday mosque—a mosque “capable of accommodating the entire male Muslim population for the Friday prayer.”5 This was the site of political rallies, public announcements, the appointment of public officials, funerary prayers, and it also served as temporary housing for the poor.6 The idyllic landscape depicted in the mosaics seems to give visual form to the words of al-Walid’s speech. As it turns out, al-Walid’s proclamation was more than just rhetoric—the mosque still stands, attracting numerous pilgrims and visitors and asserting the prowess of the Umayyad rule.7

A phenomenal video showing the evolution of the monuments on this site—from the original construction to its present appearance—is available at: http://www.qantara-med.org/qantara4/public/show_video.php?vi_id=99.

Annie Labatt is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Saint Antonio specialising in the development of Christian iconographies in Byzantine and Medieval art. Labatt was the 2012 Chester Dale Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s department of medieval art and the cloisters.

Follow us on Twitter @DimashqJournal

References

[1] Flood, The Great Mosque, 1.

[2] Hillenbrand, “Great Mosque.” Grove.

[3] The Qibla is the direction that should be faced during prayers and is fixed in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca.

[4] Flood, 2001, 250. “Then let man look at his food / (and how We provide it): / For that We pour forth water in abundance, / And We split the earth in fragments, / And produce therein corn, / And grapes and nutritious plants, / And olives and dates, / And enclosed gardens, dense with lofty trees, / And fruits and fodder…” (Sura 80)

[5] Flood, Byzantium and Islam, 248.

[7] Flood, The Great Mosque, 1

Bibliography

Bahnassi, A. The Great Omayyad Mosque of Damascus: The First Masterpieces of Islamic Art (Damascus, 1989)

Brisch, Klaus. “Observations on the Iconography of the Mosaics in the Great Mosque of Damascus.” In Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World, edited by Priscilla P. Soucek, 131–37. University Park, PA., 1988

Evans, Helen C. Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012, passim

Flood, Finbarr B. “Faith, Religion, and the Material Culture of Early Islam.” In Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. 244–258.

———”Umayyad Survivals and Mamluk Revivals: Qalawunid Architecture and the Great Mosque of Damascus.” Muqarnas 14 ( 1997 ), 57–79.

———”Light in Stone: The Commemoration of the Prophet in Umayyad Architecture.” In Bayt al-Haqdis, vol. 2, Jerusalem and Early Islam, edited by Jeremy Johns, 311–59. Oxford, 1999.

———The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture. Leiden, 2001.

Grafman, R. and M. Rosen-Ayalon: “The Two Great Syrian Umayyad Mosques: Jerusalem and Damascus,” Muqarnas, 16 (1999), 1–15

Hillenbrand, Robert. “Great Mosque.” Grove.

Mango, Marlia. “Damascus,” The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Ed. Alexander P. Kazhdan. © 1991, 2005 by Oxford University Press, Inc. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: (e-reference edition). Oxford University Press. Yale University. 17 February 2012 http://www.oxford-byzantium.com/entry?entry=t174.e1343

Ratliff, Brandie. “Christian Communities during the Early Islamic Centuries.” In Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. 32–41.

Walker, Bethany. “Commemorating the Sacred Spaces of the Past: The Mamluks and the Umayyad Mosque at Damascus.” Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 67, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), 26–39