The Ain al-Fijeh Company and the birth of Syrian economic nationalism

Dimashq Blog | Fadi Esber

Over the past 12,000 years, Damascus has grown from an agricultural settlement populated by several hundreds early farmers to a bustling metropolis of over six million people. One fact, however, remained unchanged: Damascus could not have existed, and would not continue to exist, if it was not for the Barada River. The river flows down from the Ain al-Fijeh spring, located in the ridgelines of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, some 25 kilometers west of Damascus. Every spring time, the snow covering mountaintops would melt, and shortly after, the Ain al-Fijeh spring explodes, sending its waters down to Damascus, heralding a season of rebirth, an occasion on which ancient Syrians celebrated the death and resurrection of the pagan god Adonis. The river descends the narrow “Rabwe” gorge before it divides into seven branches, which antedated the seven gates of the city, to irrigate the orchards of Ghouta, a green belt of lush farms embracing Damascus, before all traces of the river eventually disappear into the Syrian Desert.

From the days of early pioneers who gave up hunting and gathering and settled in the Barada River basin, to modern day Damascus with its packed apartment blocs and crowded suburbs, the waters of Barada, flowing down from Ain al-Fijeh have brought life and prosperity. Over twelve millennia, the river itself was the direct source for dirking and irrigation, and the city’s population had slowly grown from few hundreds to about 160,000 inhabitants in 1920, the year the country fell under the mandate of France. The steadily growing population of Damascus, recovering from the horrors of famine during World War I, and the burgeoning modern economy, coupled with the overreliance on the river as the sole water source, however, led to water shortages and unsanitary conditions. In wake of the mounting crisis, the French mandate authorities planned to set up a modern water system that would bring fresh water directly from Ain al-Fijeh into the city, and French companies were set to carry out the project.

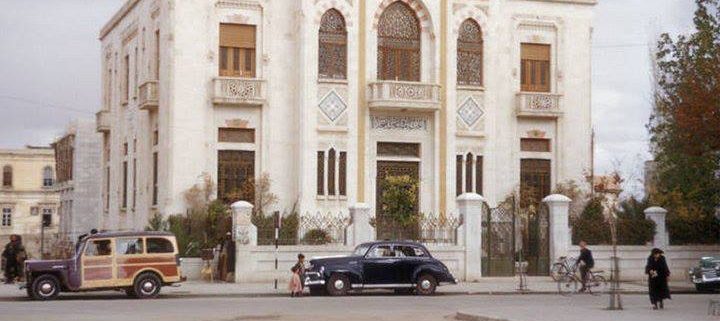

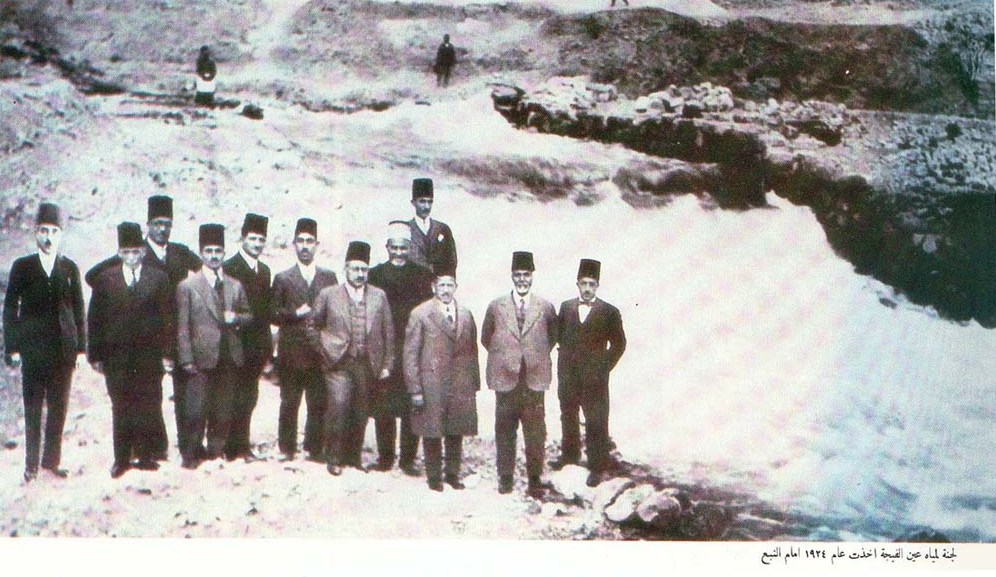

The thought of Damascus’ water supply falling under foreign ownership provoked uproar among the city’s political and business class. In 1922, a group of the city’s businessmen, led by notable merchant turned politician Lutfi al-Haffar (1891-1968), established the Water Owners Association. The group petitioned the Government of Damascus to establish a Syrian-owned, Syrian-run company to pump the fresh water of Ain al-Fijeh directly to Damascus, and in 1924 the Ain al-Fijeh Waterworks Company was established. The endeavour first relied on money gathering, and the company was divided into 5000 shares, priced at 30 golden liras each, which secured 150,000 liras in funding. The construction cost, however, was almost double the initial estimate, reaching 270,000 liras. The additional costs were covered by the Government of Damascus, which bought 1500 extra shares, and by renting out the al-Hamah waterfall, which was created by dumping the excess waters of Ain al-Fijeh, to a Belgian company that would employ it to generate hydroelectricity. The project was concluded in 1932, and al-Haffar became its general comptroller, a position he held until 1958.

The Ain al-Fijeh Waterworks Company became the first public-private ownership company in the history of Syria, and a testament to both the strong nationalist sentiment and the economic ingenuity of Damascus’ notables. The company became a model for many future projects and guaranteed national control of vital resources in times of unforgiving colonial rule. The constant and direct flow of fresh water not only revolutionised the city’s infrastructure, allowing for urban expansion and economic growth, and improving agricultural output in the Ghouta region, but also generated wealth for the inhabitants of Damascus and the public treasury. Above all, the Ain al-Fijeh endeavour proved once and for all the erroneousness of France’s claim that Syrians were unable to rule themselves and were therefore in need of a foreign mandate.

Fadi Esber is the editor of Dimashq Journal

Follow us on Twitter @DimashqJournal